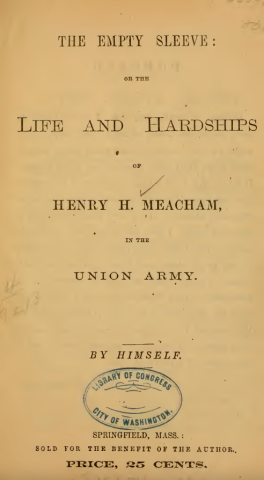

“Having lost my right arm, which excludes me from most kinds of work, I have taken this method of gaining a living... I throw myself upon the generosity of the public.”

- The Empty Sleeve: Life and Hardships of Henry H. Meacham of the Union Army. By Himself.

When representatives of the United States Sanitary Commission began to think about how to help soldiers who were permanently disabled by the Civil War, they did what the organizers of deaf schools, blind schools, and insane asylums had done in earlier decades. They traveled to Europe.

In 1862, Sanitary Commission President Henry H. Bellows sent Stephen H. Perkins of Boston across the Atlantic Ocean to see how European nations responded to large numbers of disabilities produced by large-scale warfare. Yet rather than copy European approaches, Perkins and the Sanitary Commission rejected them.

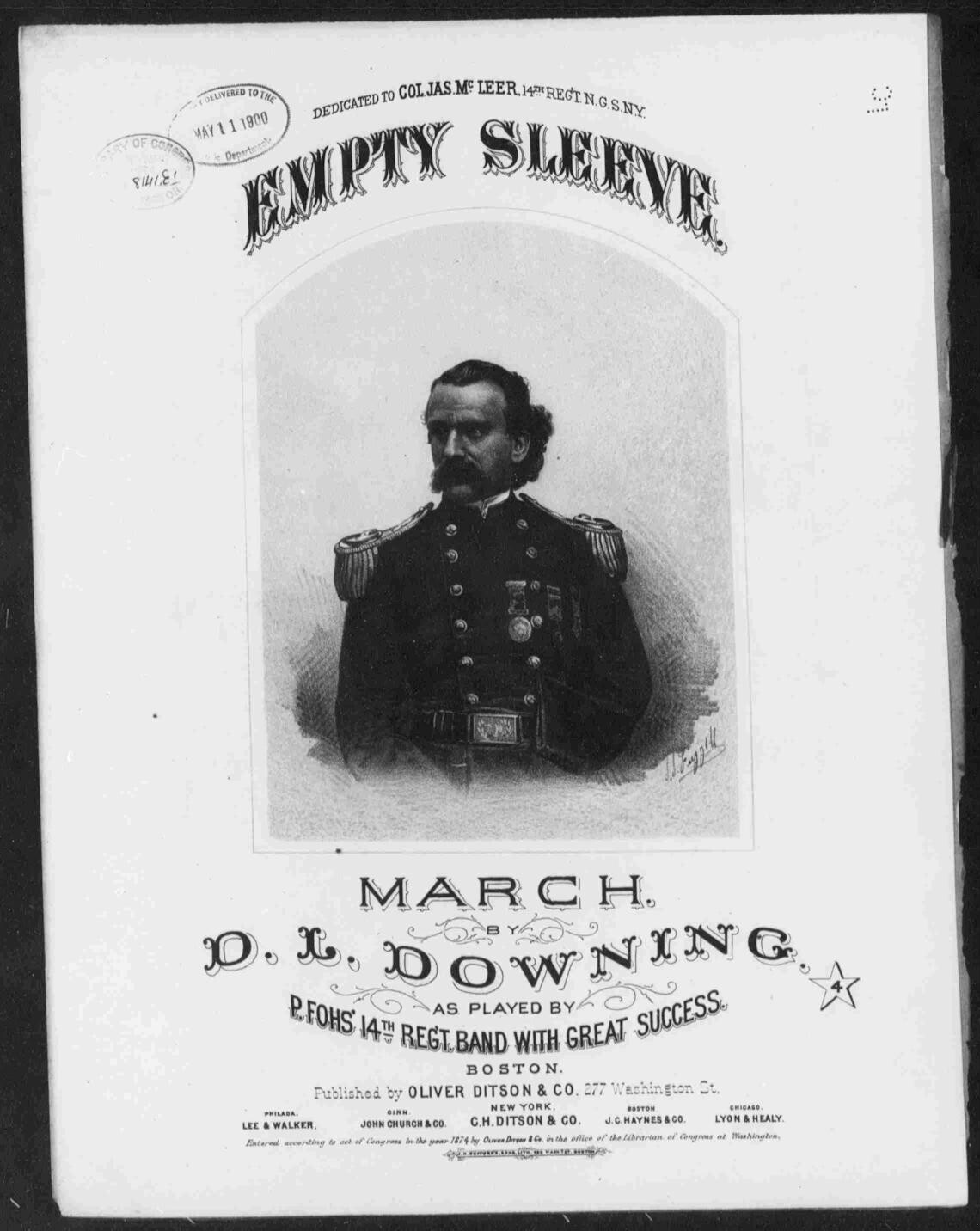

Image: DL Downing’s “Empty Sleeve” sheet music. (1874).

Perkins declared that the United States should not build large, centrally managed institutions to house veterans disabled by war. Neither should the nation make disabled veterans depend on begging to survive. Americans should “restore the large proportion of all our invalids to their homes, there to live and labor according to their strength, sustained and blessed by their own kindred.” America should discourage giving to beggars. Disabled soldiers should be cared for in loving homes, supported by generous local communities, and added to with adequate disability pensions.

Yet the story of Henry H. Meacham (1835-1879) and thousands of soldiers like him provide evidence of the failure of this ideal vision of the Sanitary Commission. Indeed, Meacham and many other veterans did end up pleading for money to strangers. Thousands became inmates at the massive National Home for Volunteer Soldiers in Togus, Maine.

When war broke out in 1861, Meacham was a carriage-maker from Russell, Massachusetts. He quickly volunteered for service, inspired “by the love of my country.” Yet he was rejected as being physically incapable of making it through the difficulties of army life. After his third examination by a doctor, Meacham was finally accepted on July 17, 1863, into the Thirty-Second Regiment Massachusetts Volunteer Infantry.

We know Meacham’s story because, after the war, he self-published a pamphlet entitled The Empty Sleeve. Sale of the pamphlet added to what he thought was too small a disability pension. In something like a nineteenth-century version of a GoFundMe site, Meacham sold copies of his story for 25 cents, stating, “I throw myself upon the generosity of the public.” The pamphlet made the case that his disability made him “worthy” of help. Worthiness became a common theme in the many political debates over the rising cost of Civil War pensions and soldiers’ homes in the last 30 years of the nineteenth century.

Meacham’s pamphlet gives details of his experiences in the Thirty-Second Massachusetts with hard marches and blistered feet, rain and cold, disease and wormy bread. His tale peaked with Meacham’s participation in Ulysses S. Grant’s 1864 bloody campaign in Virginia. On June 22, 1864, outside Petersburg, a Confederate shell killed five men from Meacham’s unit and badly damaged his arm, which had to be amputated. He walked a mile seeking medical care. Then he spent time at the City Point Hospital in Washington, D.C., and on September 1, 1864, he returned to Springfield, Massachusetts. He ended his story by asking for money based on his poverty, on his need to care for a wife in poor health, and on his inability to live on his disability pension of fifteen dollars per month. However, “should war break out again,” he offered his other arm, or his life, “to sustain our liberty and independence.”

Yet in the end, Meacham lost his own independence in the years following the war. On December 9, 1871, he entered the Togus National Home for Disabled Volunteer Soldiers. He stayed there until he was released on August 27, 1875. By the late 1870s, nearly a thousand men lived at Togus.

In 1866, the federal government purchased a former resort at Togus Springs, four miles from Augusta, Maine, for $50,000. By December 1, 1870, the government spent another $243,300 to improve the property.

The several branches of the National Home, the largest of which was in Dayton, Ohio, got a great deal of attention because of charges of abuse, immorality, and corruption. A Congressional report in 1884 on an investigation of the National Home argued that these institutions should be “homes for the country’s defenders, not asylums for the helpless poor.” Yet the report also described a deeply sad atmosphere in them. The report claimed that the managers of the National Home had to “deal with cripples, rheumatics, epileptics, dyspeptics, men who have been victims of excessive drink, depressed by a sense of advancing age and penury, men of all degrees of mental and moral development, who have no future to look to beyond the grave-yard in sight of the home.”

Meacham lived in a dormitory, ate in a large dining hall, and worked to support the National Home and himself. Togus maintained “a bakery, a butcher shop, a blacksmith shop, a brickyard, a boot and shoe factory, a carpentry shop, a fire station, a harness shop, a library, a sawmill, a soap works, a store, and an opera house theater.” There were many opportunities for paid employment.

According to people who were there, there were also many opportunities to drink alcohol. We don’t know if Meacham was a problem drinker, but many disabled veterans were. All the National Homes were surrounded by places to buy alcohol, happy to take veterans’ money. Many veterans were eager to buy. Many did become alcoholics. How much problem drinking was a direct result of traumatic experiences during the war is hard to say, but it is easy to believe.

After leaving Togus, Henry H. Meacham did not live long. He died of pneumonia in Boston on April 21, 1879, at the age of 44.His death record listed his occupation as “Peddler.”

Image: There is no known photo of Henry Meacham. In this portrait, Medal of Honor awardee Sergeant Thomas Plunkett of Co. E, 21st Massachusetts Infantry Regiment in uniform with amputated arms and “empty sleeves.” Rockwood, photographer. (c1862-1870). Library of Congress.

See the article on the Togus Soldiers Home.

See the article on the U.S. Sanitary Commission.

Sources:

- Downing, D.L. (1874). Empty Sleeve. Ditson & Co, Oliver, Boston. [Sheet music.] Library of Congress.

- Investigation of the Management of the National Home for Disabled Soldiers Volunteer Soldiers, by The Committee of Military Affairs, House of Representatives. (1885). Government Printing Office.

- Kelly, P. J. (1997). Creating a National Home: Building the Veterans’ Welfare State, 1860-1900. Harvard University Press.

- Marten, J. (2011). Sing Not War: The Lives of Union & Confederate Veterans in Gilded Age America. The University of North Carolina Press.

- Meacham, H. H. (1869). The empty sleeve: or, The life and hardships of Henry H. Meacham, in the Union army. Springfield, Mass., Sold for the benefit of the author.

- Perkins, S. H. (Stephen H., & United States Sanitary Commission). (1863). Report on the pension systems, and invalid hospitals of France, Prussia, Austria, Russia, and Italy : with some suggestions for the best means of disposing of our disabled soldiers. New York : Wm. C. Bryant & Co., printers.

- Rockwood, photographer. [1862-1870]. Sergeant Thomas Plunkett of Co. E, 21st Massachusetts Infantry Regiment in uniform with amputated arms. 839 Broadway, N.Y. Library of Congress.