Few Americans in 1861 recognized the potential psychic costs of large-scale warfare. Diagnoses like shell shock, combat fatigue, and post-traumatic stress disorder did not appear until the twentieth-century. Nineteenth-century psychiatrists, largely the group of men who supervised a growing number of specialized asylums, used different words to describe causes of what they called “insanity.” In the Journal of Insanity, some of these men even argued that the war would give people purpose and common cause, so that war would be likely to reduce insanity. Not surprisingly, however, the Union Army was forced to respond to the large number of its soldiers who did experience psychiatric disorders, especially after horrific battles like Fredericksburg, Gettysburg, and Cold Harbor. The first option was the Government Hospital for Insane Soldiers in southeast Washington, D.C. Civil War soldiers, and later veterans, went there in large numbers.

Opened in 1855, the Government Hospital, (now called St. Elizabeths Hospital), expanded rapidly during the war. During the Civil War, the institution was the nation’s only federal mental health care facility. Before the war, many asylums created or expanded thanks to lobbying by Dorothea Dix were either state or private institutions. Indeed, in 1854, when Dix got Congress to pass a bill to give federal support for asylums, President Franklin Pierce vetoed it to keep the federal government from taking on any such responsibility.

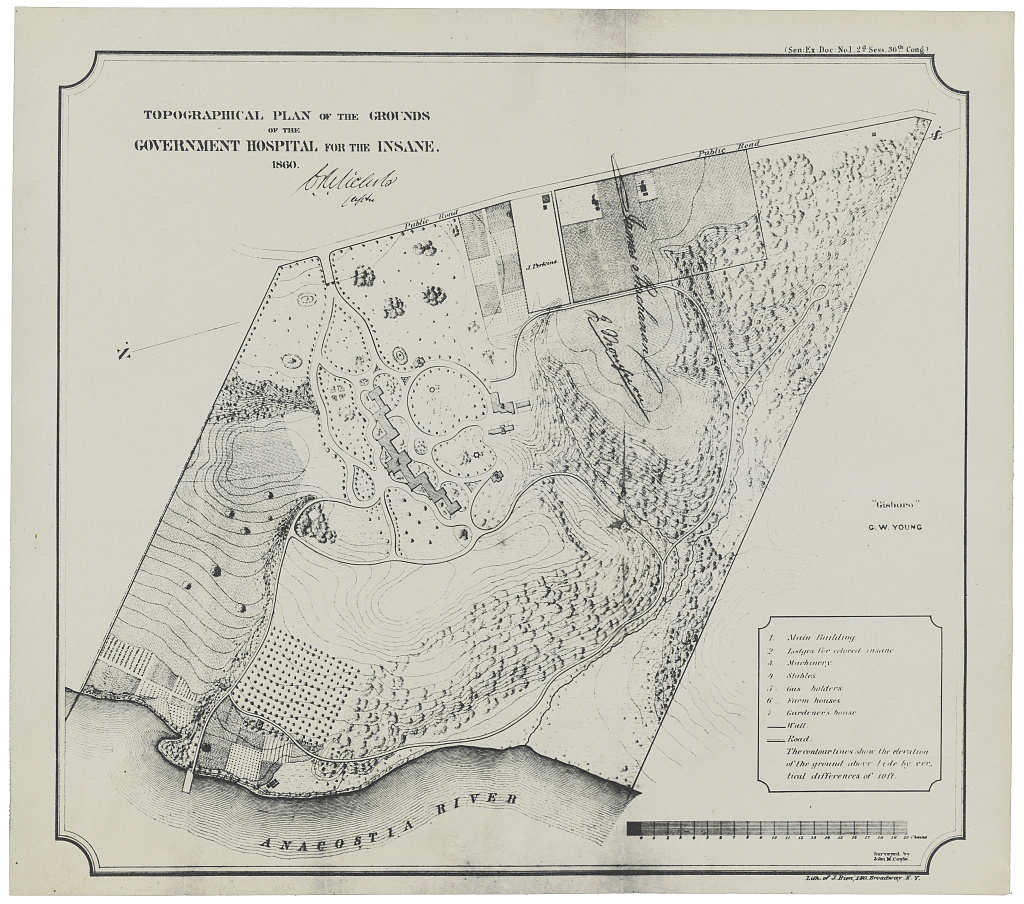

The Government Hospital was founded on the principles of moral treatment, the idea that people with psychiatric disabilities could be nurtured back to psychic health by being cared for in home-like settings with spacious, parklike grounds. Dr. Pliny Earle, originally from Leominster, Massachusetts, and one of the most prominent psychiatrists of the nineteenth century, served there during the war.

Soldiers who exhibited signs of psychiatric disorders were often suspected by officers of being lazy “malingerers.” Such attitudes persisted after the war. Veterans with psychiatric disabilities found it far more difficult to win approval for their pension application than, for example, an amputee. Dr. Earle, on the other hand, treated soldiers who were admitted to the Government Hospital as truly needing help.

As the war went on, the need grew. The Hospital admitted 212 patients in 1862 and 357 in 1863. According to Earle, the staff was overwhelmed. By the spring of 1864, the Government Hospital for the Insane held 569 patients, far beyond its capacity. Such overcrowding must have rendered moral treatment’s aspirations for a homelike environment impossible.

After the war, the Government Hospital for the Insane continued to care for Civil War veterans with psychiatric disabilities. In 1882, Congress authorized that those insane veterans housed in the branches of the National Home for Disabled Volunteer Soldiers be transferred there. Many were chronic cases, and hundreds of Civil War veterans with psychiatric disabilities are today buried on the hospital grounds. Optimistic expectations that institutions would cure insanity proved to be unrealistic.

Sources:

- Carroll, Dillon. Invisible Wounds: Mental Illness and Civil War Soldiers. Baton Rouge: Lousiana State University Press, 2021.

- Dean, Eric T., Jr. Shook Over Hell: Post-Traumatic Stress, Vietnam, and the Civil War. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1997.

- Carol Highsmith. St. Elizabeths Hospital is a psychiatric hospital in Southeast, Washington, D.C.. Photo. 2019. Library of Congress. https://www.loc.gov/item/2020720076/.

- Government Hospital for the Insane, Grounds. (1860). Library of Congress. https://www.loc.gov/resource/ppss.00882/.

- Logue, Larry M., and Peter Blanck. Heavy Laden: Union Veterans, Psychological Illness, and Suicide. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2018.

- Sanborn, F.B. Memoirs of Pliny Earle, M.D., with Extracts from His Diary and Letters (1830-1892) and Selections from His Professional Writings (1839-1891). Boston: Damrell & Upham, 1898. https://archive.org/details/memoirsofplinyea00sanb.